Banking Behavioural Design

The Annual Millennial Review demonstrated that 46.8% of respondents saw savings as their greatest financial challenge. This report outlines a behavioural nudge that banking institutions can incorporate to mitigate the impact of spendthrift behaviour.

Consumer behaviour deviates from notions of perfect rationality, frequently demonstrating choices that render suboptimal outcomes. Excessive spending/consumption are behaviours that occur all too easily and are largely he result of cognitive and emotional biases. Susceptibility to biases is prevalent in financial decision making and in many cases, acknowledgement of these biases alone will prove insufficient in overcoming their influence.

We must therefore consider what we can do to mitigate the influence that a lack of self-control can have on consumer spending.

The concept of Mental Accounting was established by Richard Thaler (1985), which recognised that the theory of fungibility was being readily violated (‘the notion that money has no labels’ (Thaler, 1990, p.194)). Thaler’s findings highlighted that consumers demonstrated a greater propensity to spend money received from tax returns or gifts, on items that they otherwise wouldn't ordinarily purchase. Mental accounting demonstrates that consumers see windfall gains in a different light to their salary earnings. A dollar is a dollar irrespective of its source however, different sources resulted in different consumption behaviour. The theory builds upon Kahnemam and Tversky’s Prospect Theory (1979) which suggests that individuals measure a gain/loss relative to a reference point.

With both Mental Accounting and Prospect Theory demonstrated to be innate in human behaviour, it is possible to design a system which deliberately adjusts the 'reference point' from which gains/losses are evaluated. If an individual has a bank account with $10,000 and they go out for a $250 dinner, the pain of parting with the $250 is in part measured by the deviation from the $10,000 reference point. Imagine now that the consumers bank account was structured so that the $10,000 was apportioned into 3 different accounts; entertainment ($1,000), bills ($6,000) and investment ($3,000). The $250 dinner would draw from the entertainment account thus the consumer will measure the pain of parting with the funds relative to the $1,000 reference point. Illustrating the point in percentages, despite the consumer having the same net wealth in both scenarios ($10,000), the $250 expense is experienced significantly differently; a 2.5% deviation from the reference point in the first scenario compared to a 25% deviation in the second.

Opening an ecosystem of bank accounts creates category specific budget constraints, thus the consumer is forced to evaluate purchases differently (Thaler 1985, p. 207). A multiple account system acts as a self-control device, as rules can affect behaviour by imposing constraints (Shefrin & Thaler 1981, p. 2). This system makes the pain of spendthrift behaviour more prominent, thus inadvertently motivating more calculated financial decision-making. The behaviour that this portfolio seeks to encourage is the creation of multiple savings accounts.

WHY DON'T CONSUMERS OPEN MULTIPLE SAVINGS ACCOUNTS?

Status Quo Bias

Individuals tend to maintain their current course of action even when they are aware of a more beneficial alternative. This emotional bias predisposes decision makers to take the path of least resistance, often omitting from changing their behaviour entirely. To those who are aware of the benefits of a multiple account system, the influence of this bias may result in them failing to take action; continuing on with their current set-up of one or two accounts.

Default Bias

Default bias refers to the tendency of individuals to opt for the easiest choice. This choice may be to not act at all or to select the default option when faced with a decision. Individuals setting up saving s accounts through a financial institution often find that accounts have to be set up one at a time. The consumer may hence fall victim to this bias and perceive that the default of having one account is the recommended option, failing to take the additional steps required to create additional accounts.

Ego Depletion

Current product offerings by financial institutions require consumers to follow a number of steps to open a savings account. These onboarding processes require contact numbers, email addresses, date of birth, residential address and contain a procedure for identity verification. NeoBanks such as 86400 and Up have made significant headway in improving the timeliness of these onboarding processes without cannibalising user experience. The process for both of these banks takes less than 4 minutes, compared to CommBank’s 6 minutes followed by a 6-day waiting period (The Singularity Mesh 2020). Notwithstanding these improvements, the onboarding process still exacerbates decision fatigue. At the completion of the onboarding, customers will often have only opened one single account thus additional steps must be taken in order to completely fulfil the multiple account strategy. Due to the effects of decision fatigue, there is a strong likelihood that the additional steps required to set up more accounts, will not be completed.

BEHAVIOURAL INTERVENTION

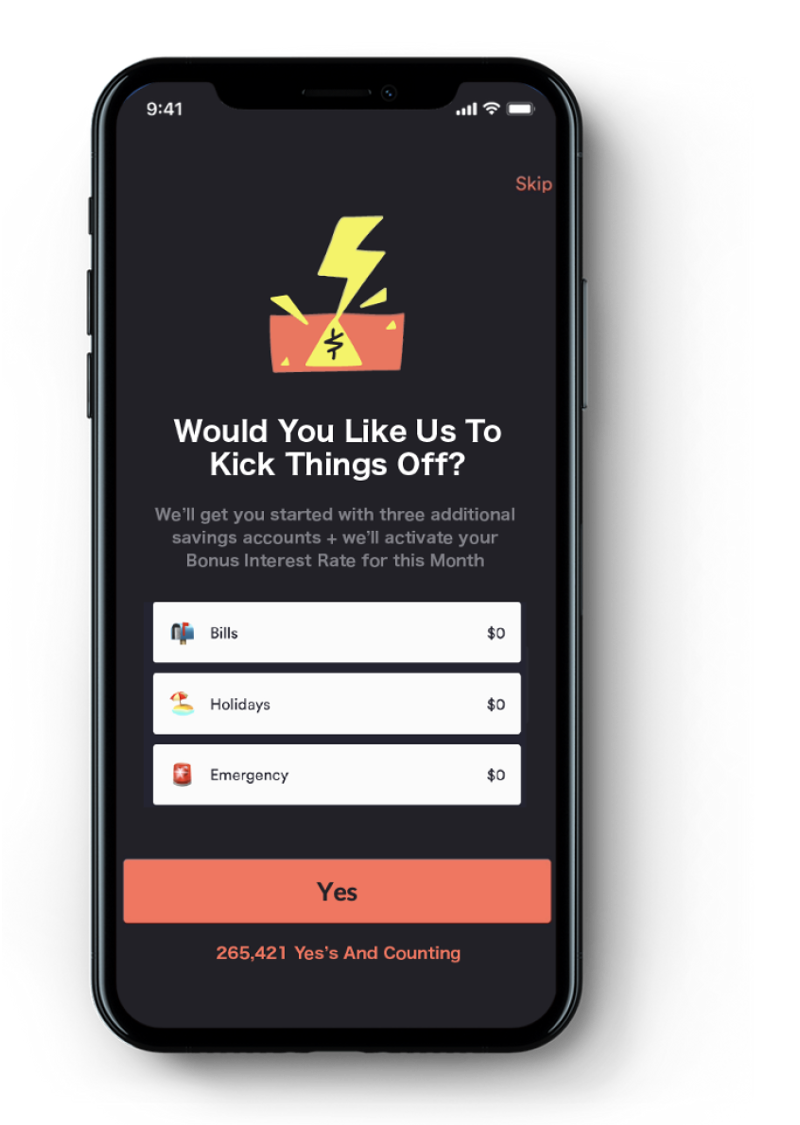

The above-mentioned frictions act as barriers against engagement with the multiple account strategy. The proposed behavioural design intervention is one that can be implemented by financial banking institutions. This recommendation utilises the Up Bank App to demonstrate the design however the premise is not limited to one bank. In order to remove the effort and cognitive load required to set up multiple accounts, it will be beneficial to break down the steps required to establish this system. In order to do this, it is recommended that UP attempts to nudge its consumers to adopt the strategy during the new customer onboarding process. The image above is the proposed additional step.

The proposed behavioural design technique utilises a default option, positioned in the final stages of the onboarding process. At the completion of most 'new customer onboarding processes', the consumer will have opened one/two savings accounts. This default option is designed to prompt the consumer to finish the onboarding process with a full ecosystem of category specific accounts rather than the normative one/two.

A controlled trial in Germany tested the effect of a default nudge on the uptake of a more expensive, 'Green Energy' offering when signing up to an energy provider. Setting the default choice to the 'Green Energy' option increased purchases of such nearly tenfold (Ebeling, Lotz 2015, p. 868). This default option strategy has also demonstrated significant success in prompting charitable donations. Manipulating the default, yielded statistically significant effects on the targeted behaviour (Ghesla, Grieder & Schmitz 2019, p.2), increasing the frequency and size of donations.

In addition to reducing frictions, this alternative is designed to attract the consumers attention. The screen itself is structured to make the affirmative option the easiest to select by anchoring the bright orange, full width button to the bottom of the viewport; close to your thumb and easy to hit (Wearne, 2020). By placing the opt out feature (‘Skip’) in the top right-hand corner, the consumer must put in more effort to select it. Marginally increasing the effort required to select the non-preferred option is deliberate. This is because effort is a ‘prime factor in preventing individuals [from changing] pre-set choices’ (Ghesla, Grieder & Schmitz 2019, p.6).

To incentivise the affirmative behaviour, this strategy offers to activate the bonus interest rate for a month (normally activated after a volume of transactions). This monetary incentive is only obtainable if the customer opts-in and further engages with the strategy. To profit from the incentive, the consumer must transfer funds into the savings accounts thus prompting greater participation with the overall strategy (interest received is intrinsically linked to the amount of savings in the accounts).

The participation statistics recorded underneath the ‘Next’ option highlights the extent of engagement from society, tapping into the power of social herding. Utilising such a tool helps the default effect to focus on social norms; implying endorsement from others (Sintov & Shultz 2017, p. 4). Selecting the ‘Skip’ option would hence represent a departure from the norm, implying the possibility of social rejection (Sintov & Shultz 2017, p. 5). Given the human tendency to 'make decisions based on what the crowd is doing' (Centre for Advanced Hindsight 2015), showing the prospecting consumer that the ‘herd’ has opted-in may encourage them to do so as well.

The timing of this strategy is equally as important to the structure of its design. This nudge is presented whilst a consumer is engaging with a new bank thus their existing habits are already being disrupted. Adapting Thalers premise of integrating losses, by integrating the disruptions, the experience of the overall disruption is reduced (Thaler 1985, p. 202). As previously mentioned, the 4-minute on boarding process elicits a degree of ego depletion hence it is likely that consumers will not follow through and set up additional accounts upon completion. The positioning of this strategy at the end of the onboarding process uses the consumers decision fatigue to the strategies advantage. Being fatigued, the consumers susceptibility to opt-in to the default is increased for the simple reason that it requires the least mental effort.

This strategy optimises the probability that consumers open multiple, category specific savings accounts. The placement of the strategy in bank's onboarding processes will make the nudge available to all consumers, including the unadvised category. With multiple accounts, a large consumer base will have a system in place that is designed to recode spending experiences, promoting more stringent financial decision making.